My great grandmother was the meanest woman ever. To read the first installment of her story read here.

By the age of 18, Annie was already the survivor of a short-lived disasterous marriage.

During the two summers of 1879 and 1880, Annie worked for the Houston families at their ranches. This is where Annie first met Joesph Houston, a grey-eyed handsome rancher. Joseph was a widower who was nine years older than Annie.

In 1874, Joseph had married his best friend’s sister, Elizabeth Clark. Joseph’s best friend, Riley Garner Clark II, married Joseph’s younger sister Margaret in a double wedding. Elizabeth died in childbirth in 1879, leaving Joseph with two small children.

Joseph Houston in about 1887

Joseph Houston in later life

What drew Joseph and Annie together? For Annie, Joseph likely offered respectability and financial stability. The Houstons were wealthy and prominent citizens (Joseph would go on to serve two terms as mayor).

Joseph and Annie married in January 1881.

In the following twenty-four years, Annie gave birth to twelve children:

- Josephine (nee Connor Hilton)(1881 – 1953)

- Maria Dempster (nee Fotheringham)(1883-1953)

- Joseph (1885 – 1885)

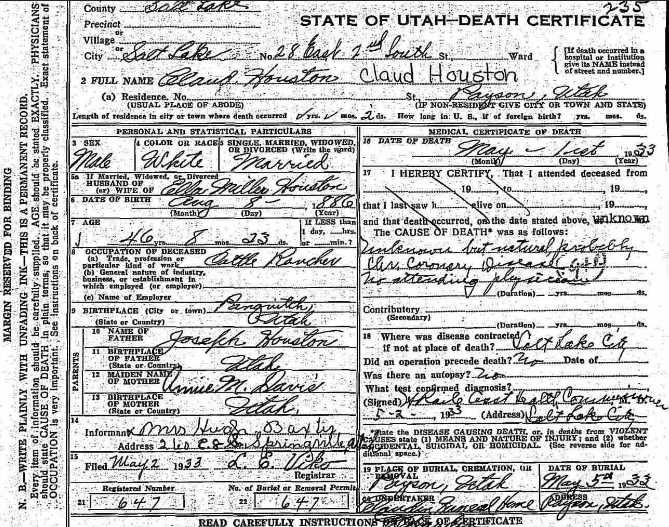

- Claudius (“Claud”) (1886-1933) b

- Margaret

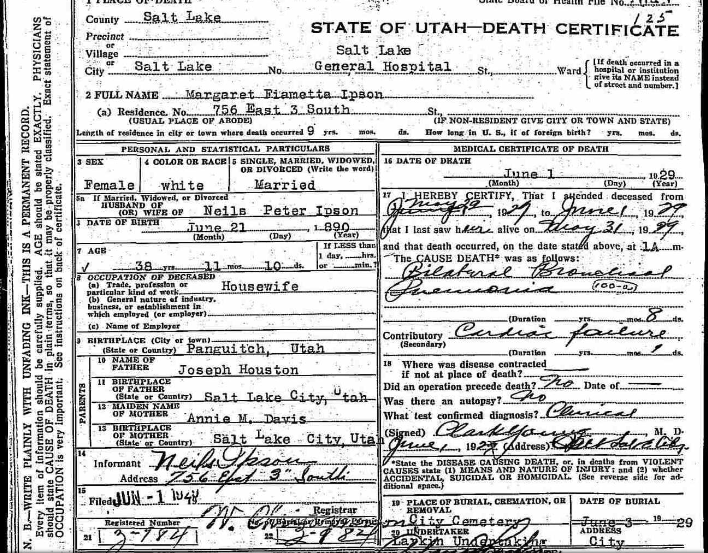

Fiametta (nee Ipson) (1890 – 1929) - Arthur Quince (“Quince”) (1892 – 1970)

- George Rollo (“Rolley” or “Roll”) (1894 – 1975)

- John Steiner (“Steiner”) (1896-1964)

- Mary Gwen (“Gwen”)(nee Baxter)(1898 – 1965)

- Thomas Ray (“Tom”)(1899 – 1970)

- Ellis Dudley (“Ellis”)(1902 – 1939)

- David Cameron (1905 – 1905)

Annie with her three oldest living children in about 1886

Seven of Annie’s twelve children (circa 1900)

“[Annie’s] one big ambition was that her family would be a credit to her and her work.”

Della opined, “I think she [Annie] was a frustrated, broken-hearted woman. Her husband didn’t show much love or respect. Always spoke of her as ‘the other woman’. His Johnny ways annoyed her. She was very proud and wanted her sons to be in prominent positions in the town.”

In his own words when discussing his love of reading, Joseph said,

“My wife (Annie) was always put out about my reading. [P]erhaps I didn’t talk enough to her.”

One thing that is evident about Annie’s life is that she knew how to work and valued hard work in others. Annie was described by her daughter as “very industrious; she disliked seeing others idle”. In addition to her housework duties, Annie made rugs, quilts, crotched lace, knit stockings, and made most of her children’s clothing.

Annie and her family spent the summers on the family ranch making cheese and butter. One summer, Annie reportedly made seven barrels of butter weighing 350 lbs a barrel. This was before mechanical separators were widely available, so in addition to milking cows, Annie would distribute milk into pans, skim the cream, and churn the butter by hand.

Annie was a devoutly religious woman. She was an active member in her LDS ward and loved genealogy and temple work. For over 45 years she sang in the ward choir.

Sadly, even in her religious devotion, Annie’s pride got in the way. Joseph and Annie had two sons who went on LDS missions. Then as now, sons serving missions is a source of pride for Mormons. Quince came home after his mission president questioned why he had not been drafted (WWI); Roll completed his mission but joined a different religion soon after returning home. When Steiner asked for his parents’ support to go on a mission, they refused.

Of all of Annie’s children, only Steiner would remain an active member of the LDS faith.

By 1930, only three of Annie’s sons (Quince, Tom, and Steiner) lived in Panguitch. The other six children had moved away.

My Mom tells that as children they would beg to go to see their Houston uncles. Steiner would go, but they would stay for only a few minutes and then go home. Even when traveling, Steiner would opt to stay with his wife’s sister rather than stay with his own sister, who lived a few blocks away. While Della and Steiner would have Annie and Joseph to dinner nearly every Sunday, the family get-togethers were always initiated by Della and not Steiner.

The last years of Annie’s life were lonely ones. In 1929, Annie’s daughter Margaret Fiametta died at the age of 38 from pneumonia. In 1932, her son Claud died at age 46 from a heart attack. In 1935, her

Most tragically, in 1939, Annie’s youngest son, Ellis died at the age of 35 as a result of injuries he sustained in a car accident and from exposure. Ellis was an alcoholic.

When Ellis came home drunk and Annie would tell him he had to go elsewhere, Ellis would threaten that he would leave forever and someday when Annie heard about a vagrant getting killed she would always wonder if it was her baby boy.

On the late December day when Ellis was in the car accident that ultimately would take his life, he came home drunk and injured and pounded on the door yelling for Annie to let him in. Annie didn’t let Ellis in. Ellis contracted pneumonia as a result of exposure, which led to his death a month later.

Annie’s neighbor and friend, Cecil Reid said that Annie would feed the neighbor’s chickens to coax them so that she could see them. When asked why, Annie said, “To watch something alive and moving”.

Annie rattled around her grand brick home filled to the gills with stuff she couldn’t bring herself to throw away. The kitchen cabinets were full of kindling, cupboards and containers were full of rags (including cut up pockets of men’s overalls), as well as “great balls of string” that she had saved. After her death, Annie’s children “hauled truckloads of junk to the river.”

Annie died on July 23, 1941, two months after she suffered a stroke which left her bedridden. Her obituary is titled “Pioneer Woman Buried Saturday Afternoon: Was Active in Church Organization in Life – Member of Choir”. All of Annie’s living sons and daughters were in attendance.

The story continues here.