This post is the final post in a series on building context for the events in your ancestor’s lives. Read the first installment here. In the last post, I discussed how phone directories, maps, and photos add geographic context to a 1918 Salt Lake Tribune newspaper article where George Neuman was required to obtain “zone privileges” to work as a butcher.

Finally, personal context

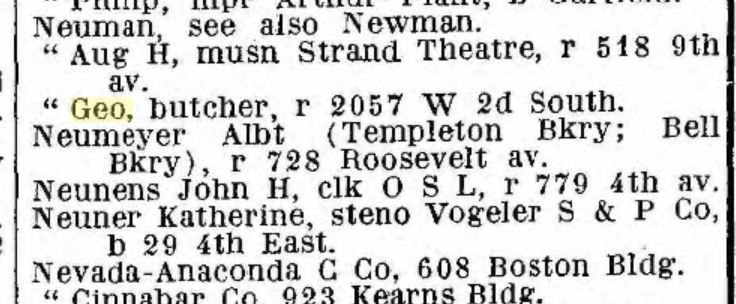

During the course of 1917-18, George Neuman changed residence and also changed employers all during a time when unnaturalized Germans were subjects of suspicion and outright surveillance. Remember, a fellow sausage maker, Max Graeske, who worked in the same area of town as George (also information we can ascertain through the City Directory) was interned as an alien enemy at Fort Douglas.

We won’t ever know definitely if the permit requirements of 1918 influenced George’s decision to change employment and residence. There is, however, one final indicator of how this uncertain time influenced George.

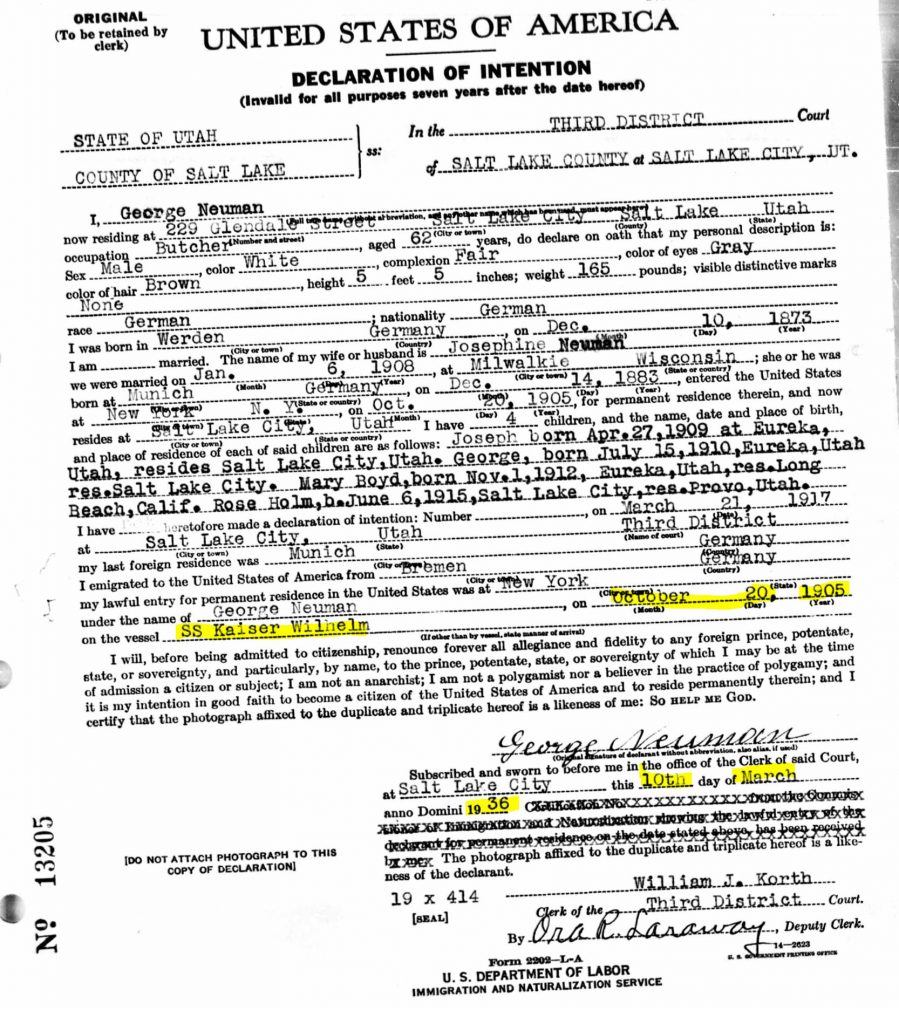

In March 1917, just a few days before the U.S. entered into WWI, George filed a Declaration of Intention to become a citizen. At the time, this was the first step of becoming a U.S. citizen. Of note, in his Declaration, George identifies his date of entry into the United States as October 20, 1896.

However, George did not complete his naturalization in 1917 or in the years that followed. According to the Zone Privileges article no Germans were granted naturalization during WWI.

However, George waited another nineteen years to pursue naturalization. In March 1936, in the lead up to another world war with Germany, George again filed a second Declaration of Intention.

This time, George identifies his date of arrival as October 20, 1905 (Ship Manifests indicate he likely arrived on November 15, 1904). Perhaps not coincidentally, George’s first Declaration, which was filed at a high point of anti-German sentiment, indicated he entered the U.S. eight years earlier than when he actually entered the country.

George eventually gained citizenship on June 27, 1941, just six months prior to the U.S. entry into WWII.

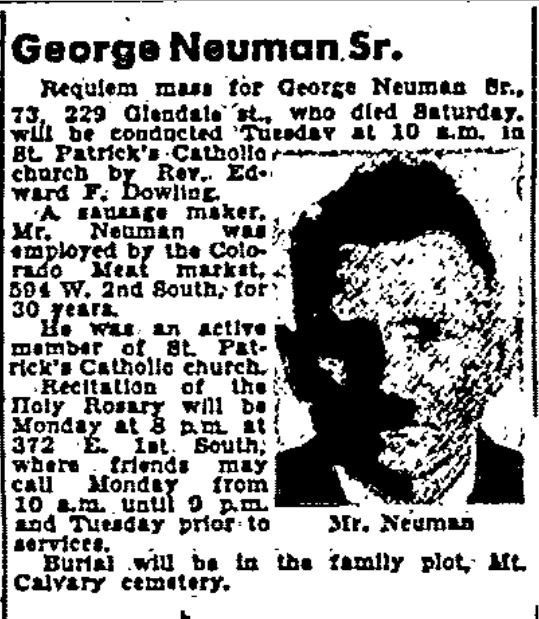

George died in 1947, just six years after becoming a U.S. citizen.

Through the historical context, surrounding articles, geographic knowledge, and the personal events in George’s life we are able to gain much greater insight and understanding of how one event may have shaped George in 1918.

For me, gaining a greater understanding of how singular events in an ancestor’s life fit into the larger context is one of the primary goals of family history. It is only by adding context that a richer picture of our ancestors’ lives can be achieved.